At PBE’s Economics to improve lives event last week, we were joined by a fantastic panel to talk through the findings of our report “Caught in a trap? Low wellbeing in the UK 2025”. In this blog we discuss one of the big questions that was raised by attendees – whose job is it to improve the nation’s wellbeing?

The wellbeing challenge for the UK

Our latest analysis suggests there are almost 3 million adults in the UK living in wellbeing poverty (responding with a score of four or below out of ten to the ONS’s standardised wellbeing question “Overall, how satisfied are you with your life?”) Put into context, this equates to a population roughly the size of Northeast England, struggling with life.

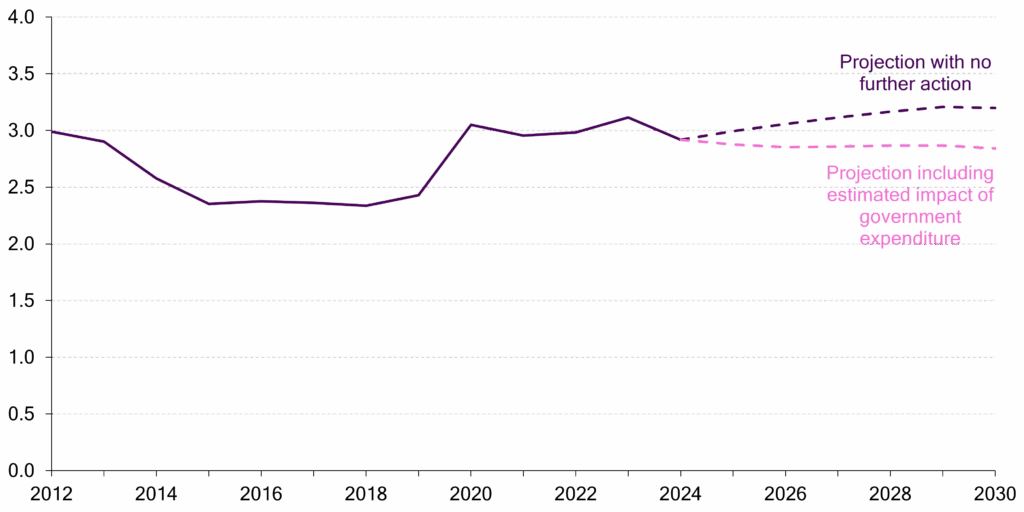

Worryingly, this number appears to be stuck at a level almost half a million higher than it was prior to Covid and is likely to get worse without further action. Our analysis suggests that deteriorations in the nation’s physical health, mental health and loneliness can explain much of the increase in wellbeing poverty in recent years. If these trends continue with no further action to counter them, then they are likely to result in a further 300,000 adults living in wellbeing poverty by 2030.

Figure 1: The number of people in wellbeing poverty likely to remain higher than in 2019

Number of adults with low wellbeing, millions

Source: PBE analysis of Annual Population Survey (2025)

PBE believes that a decade-long stagnation in the nation’s wellbeing is not acceptable. We can and should take action to halt and turnaround the deteriorating trends in the key drivers of wellbeing such as physical health, mental health and loneliness – but who needs to take this action?

What role does the government have?

If, as one of our panellists suggested, the government committed to a “comprehensive wellbeing review” alongside its comprehensive spending review, it would start to drive down levels of wellbeing poverty in the UK. However, in the absence of this clear focus, and during a period of overstretched budgets and overloaded public services, can we rely on the government to achieve this?

Our analysis suggests that, even with strained public budgets, decisions about government spending still matter. The recent spending review’s commitments to increase investment in health and social care could help to push back against the wellbeing headwinds that the UK faces. However, even with this boost in support for our physical and mental health, the number of adults living in wellbeing poverty will likely remain at a higher level than we saw prior to the pandemic.

But it’s not just about what the government spends money on. As discussed in our report, legislative changes such as the Renters Rights Bill also have potential to impact on the nation’s wellbeing by reducing levels of instability faced by millions of private renters – a group that is far more likely to experience low wellbeing. In addition, the convening role that central and local government often play could also be critical in drawing cross-sector insight to find solutions.

However, as highlighted in Sarah Davidson’s article from our Economics to improve lives article series, “there is increasing frustration that despite the existence of holistic wellbeing outcome frameworks with accompanying indicators, there is still a palpable disconnect between policy intention and policy practice and outcomes.” Loneliness potentially provides an example of this – it is well established as a key driver of wellbeing and health outcomes. Yet, despite the 2018 Loneliness Strategy, there is a sense that there is a lack of momentum in tackling it as a public health issue. Given this, can we credibly expect the government to play a central role in targeting and reducing wellbeing?

Can the social sector fill the void?

So, if the government isn’t yet stepping up to the mark to tackle the growing stagnation of the nation’s wellbeing, is the social sector able to fill the gap?

Potentially. The sector naturally targets and supports people struggling with the lowest levels of wellbeing. Whether it’s support for people living with poor mental health, programmes to help those with disabilities or long-term illnesses to find their way back into work, or assistance for people that can no longer afford to stay in their home, the sector has the reach to make a difference to many of those people living in wellbeing poverty. Clearly, there is potential to build on the passion and expertise in the sector to make a huge difference.

However, to continue to do this work, these organisations need stable, patient funding that can support proven interventions and provide the freedom to innovate and find new solutions to complex challenges. If more funders can follow in the footsteps of the John Ellerman Foundation in setting a grant making strategy based around the drivers of wellbeing, then this may be possible.

What about business and personal responsibility?

And what’s the role of business in tackling wellbeing? There are likely to be two areas where business can play a particularly important role. Firstly, as an employer. We know that employment has a sustained positive impact on wellbeing. However, this isn’t just about looking after current staff but also providing accessible opportunities into work for groups that traditionally find themselves excluded from the labour market. This could play an important role in driving up the nation’s wellbeing. Secondly, they have a role to play in supporting vulnerable customers. For example, we know that struggling with bills can have an impact on the risks of wellbeing poverty. As a result, demonstrating compassion and patience for customers that are falling behind on their payments could also play an important role.

Finally, what about individuals themselves? Surely, we all need to take some personal responsibility for our own wellbeing? While this is undoubtedly true, it’s likely to be most difficult for those living in wellbeing poverty, who are struggling with some of the toughest challenges in life; ill health, poor mental health, loneliness are all difficult to overcome without being able to lean on the communities and institutions around us.

So, whose job is it to tackle wellbeing poverty?

Whilst this may seem like a bit of cop out, the answer is inevitably “all of the above”. Tackling deeply ingrained social trends around deteriorating mental health, physical health and loneliness will not have a simple answer. It will require a wide range of solutions. We need focused attention from government at the national and local level, a vibrant social sector with the capacity to respond to changing and complex needs, a considerate private sector and individuals that feel empowered to make changes in their lives. Ultimately, we believe that, through working together, we can make a real difference to the quality of life experienced in the UK today and drive down levels of wellbeing poverty. Not just to the levels seen in the UK before the pandemic, but to levels seen in those countries that have the very best quality of life such as Finland, Denmark and Iceland.