Nancy Hey, for Economics to Improve Lives series

The path to moving beyond GDP as the central measure of societal progress is all too often presented as a choice between finding a single new metric – such as Life Satisfaction – and multi-dimensional frameworks with a range of different measures. I believe this is a false choice. We need both simple headline measures to understand and communicate “what” is happening in society as well as a framework of supporting measures to understand “why”, and importantly “how” we can improve outcomes over time.

The need for more than just GDP

The criticism of traditional measures of economic success – like GDP, stock market performance or employment rates – is that they often fail to capture the full picture of people and society’s wellbeing. Further concerns are that they fail to deal with environmental impacts, climate change and with rapid technological shifts. This is well covered by Jon Franklin, Ed Humpherson (and Diane Coyle) in this series.

Research using a broader range of “success measures” tell us that GDP does still matter to national wellbeing, but there are other things that matter too. Some of those things are measures of economic activity that are wider than GDP, some of them are not about economic activity but provide meaning to our lives, such as social and environmental factors. For example, we have ‘hidden wealth’ like mental capital and social capital that we are not valuing enough. Often this hidden wealth is better suited to understanding bits of the economy not captured well by traditional GDP, such as the knowledge economy, as well as sectors of the economy outside of the bounds of market-focused GDP measures such as the care economy or charity sector.

Promisingly, the national conversation on economic growth has shifted over the last ten years. It now regularly explains why it is that growth matters (i.e. the purpose of that economic policy) rather than treating it as the goal itself. However, the first update to the System of National Accounts in 17 years still treats many of the factors that matter to national wellbeing as outside the economic domain. This suggests we should be satisfied with capturing these alternative measures of national wellbeing through “satellite accounts” for things like natural capital, unpaid work and of civil society too.

However, why should broader indicators of wellbeing be considered secondary to traditional measures of economic progress? Why should they be reported on less regularly and with longer time lags? As Allin & Hand argue, in ‘From GDP to Sustainable Wellbeing’, the goal should be to fit the measurement of economic performance within a broader assessment of national wellbeing and progress. GDP was originally developed as a way to respond to our post-war needs. Along with life expectancy, GDP was very effective at measuring societal progress throughout the 1900s. But it was never intended to be the only measure of progress and it has become more out-of-touch with what matters in people’s lives. National accounts for the 21st century need to reflect this and should cover Economic, Social and Environmental accounts. As Richard Stone, winner of the Nobel Prize in economics in 1984, noted in his lecture:

“The three pillars on which an analysis of society ought to rest are studies of economic, socio-demographic and environmental phenomena…”

Measuring Life Satisfaction broadens what we focus on

The Life Satisfaction measure of wellbeing can help us to position GDP and other measures of economic performance within that wider framework. One of its big advantages is that it works really well as an economic metric (the importance of employment is a particularly well established and practical finding). It also does a decent job of capturing how our physical health, mental health and social factors influence our lives. Sure, it’s not perfect – no measure can capture everything – but it provides a far more complete picture of our lives than many alternatives. For example, it manages to be sensitive to things we value personally such as our relationships. This is the currently hidden wealth of our social capital and the value of institutions that can provide resilience, playing an important role in institutional economics.

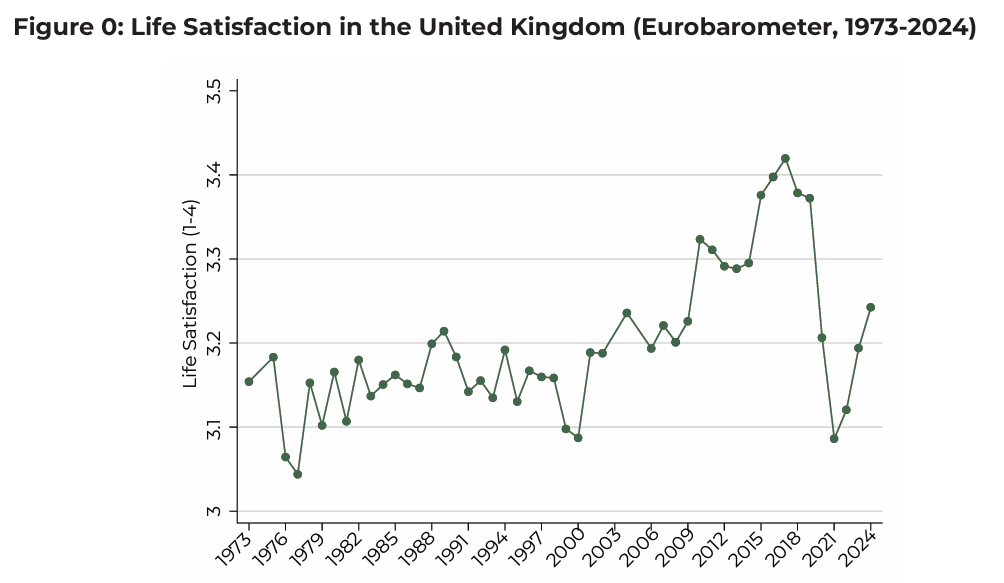

Source: The World Wellbeing Movement, UK-Wellbeing-Report-2025.pdf

But Life Satisfaction alone cannot shape policy

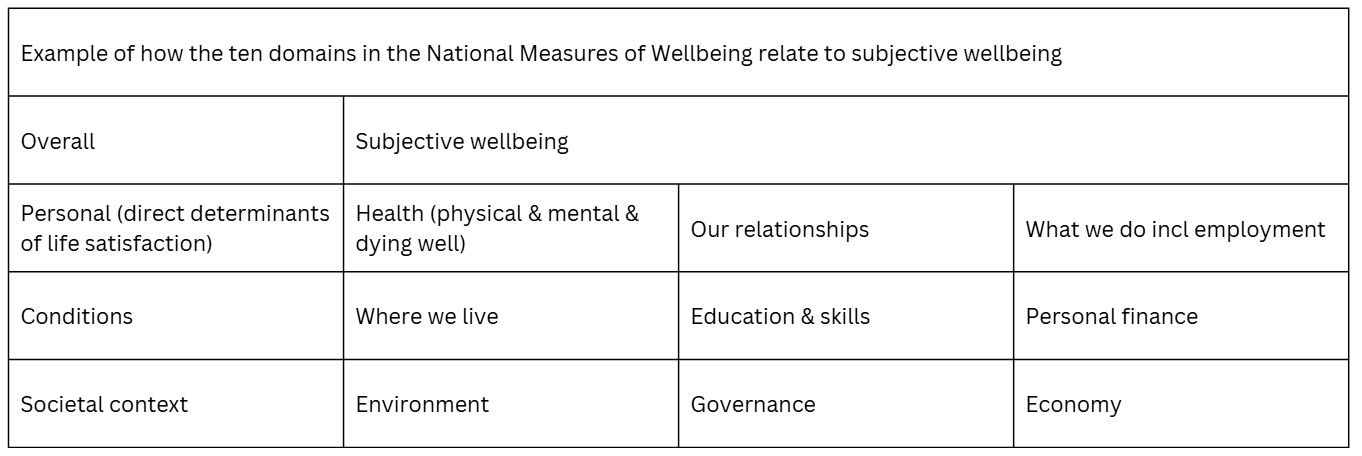

If you want to improve wellbeing or Life Satisfaction in practice, it’s important to understand why people’s wellbeing is changing and what can be done to improve it going forwards. This means that it’s critical to not only track life satisfaction, but also have a wider set of data on the drivers of wellbeing. This makes the data usable in practice, especially outside of economic policy.

This inevitably takes us into the territory of wellbeing dashboards – frameworks that pull together data on multiple domains of life and different distributional measures to provide an overall picture of ‘what matters’ to people?’. This approach often requires economists and health professionals to collaborate with other professions to understand without naivety, as some criticism of HM Treasury reflects. But when done well, it can support effective policy making. For example, the Levelling Up Industrial strategy was a National Wellbeing Strategy in all but name. Unfortunately, a big challenge on implementation was that this was forgotten and it tried to focus on wellbeing through social policy alone.

For those that advocate for multi-dimensional success measures, life satisfaction unlocks them in a practical way in order to effect change. Understanding the top drivers of life satisfaction allows us to weight and prioritise between different indicators. This prioritisation is necessary for using a limited amount of money, time and effort most effectively. Taken together these drivers can also be the key to unlocking wellbeing improvements.

The dashboard also helps tackle another criticism of subjective wellbeing in that it doesn’t move enough. Although life satisfaction can move far faster than anyone anticipated in 2011 in months and years, not decades as expected, it is slow to move and more detailed measures are needed.

Is anyone using the measures and is there any practical impact?

Multi-dimensional frameworks are not new and as both Sarah Davidson in this series and Paul Allin & David Hand in the Wellbeing of Nations highlight, there can be a perception that they have failed to change policy and societal decision making. While there is a good technical question in what successful implementation and use looks like, this apparent failure can lead critics to reject them in favour of restarting the search for a single new indicator of success.

However, I disagree that the data is not used, the challenge is that its role is often hidden from the public eye. In 15 years focused on getting subjective wellbeing and the various national measurement frameworks used, I think the data has been used very extensively. This is especially in the strategic case of setting policy objectives in government and in large parts of business and civil society. On subjective wellbeing alone, there are many examples I cover in a recent paper for the Arts Council with Daniel Fujiwara, Paul Dolan and Vidhyarth Natarajan. The same paper also outlines some of the learning from the last 15 years of the practical challenges of using subjective wellbeing in policy making

I think the use of life satisfaction as an economic policy indicator post Global Financial Crisis in the UK is what led to a sustained increase in the indicator from 2011-2017. Given the challenging social and economic environment over this period, this improvement was not inevitable. However, this tends to be ignored in large part because of the colour of the government under which it happened.

There are, however, still challenges for wellbeing frameworks. Firstly, is the way governments and much of society organise around interests such as health, education and business. Overall wellbeing also needs someone with a vested interest in remembering why we’re doing all the things and looking at what it all adds up to. Sadly, this is all too often missing. The other big challenge is that identified by the OECD in 2018 review of the Policy Use of Wellbeing metrics, of keeping the dashboards and frameworks going over time. Whilst the UK has miraculously managed to maintain its measures of national wellbeing, it is not for want of competitor models in the Health Index and Levelling Up framework. One simple solution would be for the ONS ‘front page’ to simply be the dashboard or organised by the domains of it.

The answer to these challenges seems to be:

- to keep measuring and monitoring wellbeing and its key drivers

- to make it easy to find and talk about the measures

- talk about them, ask about them and apply them

The future – progress isn’t linear

One of the challenges to subjective wellbeing, and to GDP, is that they don’t consider the future well enough. Innovations happen and, magically, techno-economic transitions happen, and things are better over time. Except we know from the inter-generational scars of technological, economic and social transitions that there are better and worse ways to do this. We also know that major gains – outcomes, or missions if you will – can be lost by economic and health events like the Global Financial Crisis, natural disaster and Covid. This is where life satisfaction, and its drivers, become useful again and were examined by the House of Lords Covid-19 Committee Inquiry into Life Beyond Covid.

To keep wellbeing sustainable for the future you need to look out for what will cause life satisfaction, and its drivers, to drop. All our ten years of progress was wiped out in months and is only now recovering to 2011/12 levels. This insight increases the importance of Capitals – stocks and flows – and of Risk and Resilience. A wellbeing state is a resilient state.

PBE, Carnegie and the World Wellbeing Movement’s recent reports on Wellbeing in the UK in 2024/5 tell the same story: that we have work to do on making life better for millions. What you can also see though is the astonishing trend from 2011/12 to 2017/18 of significant movement in subjective wellbeing in the UK. This was a deliberate targeted effort to move the dial on metrics we thought initially would move in decades; we saw in the brilliant ONS fortnightly reporting of subjective wellbeing in the pandemic that these data could move in weeks. This shows that progress is possible – and we can do it again.

This article is the fourth in PBE’s new ‘Economics to improve lives’ series that explores a question at the heart of PBE’s mission: How do we ensure that wellbeing – the quality of life experienced by individuals – is the ultimate goal of government?

We’re bringing together thinkers and commentators from across economics, policy, academia, media and civil society to challenge conventional wisdom and consider how we might build an approach to measuring economic success that puts the lived realities of people at its heart and fits the times we live in. Opinions are the author’s own.

Read previous articles in this series from Sarah Davidson, Jon Franklin, Ed Humpherson