By Jon Franklin

The Chancellor Rachel Reeves’ commitment to “go further and faster to kickstart economic growth” has cast fresh light on an old debate – does GDP (Gross Domestic Product) capture what matters? What does “growth” mean in practice? Does it reflect what really matters to people and communities grappling with rapidly increasing costs of living, climate change, declining levels of wellbeing, and global political instability?

What is GDP?

GDP measures components of economic activity in a country. It provides an estimate of the total monetary value of everything produced by businesses for a given year, as well as approximations for outputs delivered by government and some social sector organisations. Importantly it is rooted in measurements of market activity – monetary transactions between different organisations or individuals.

This means activities that occur in the household like caring for children and relatives, or preparing food, or unpaid activities like volunteering, are generally not valued because they are not goods and services that are bought and sold.

Criticism of GDP

GDP has come under increasing criticism over time. The challenges include:

- The extent to which it captures what matters to people. For instance, a wildfire that destroys homes is likely to boost GDP as the rebuilding efforts require more ‘production’.

- The inequalities embedded in what is included and what is excluded in its definition. For example, a disproportionate number of activities traditionally completed by men are included.

- Its narrow focus on output that does not acknowledge longer-term or full impacts on societies, markets and our climate.

- Its inability to accurately capture the value of increasingly important service and finance industries. The value of financial services is essentially based on the amount of risk it takes on.

There is a huge spread of views on GDP’s effectiveness as a measure. Some acknowledge its shortcomings but view it as better than any other available alternative. Others believe the measure needs to be abandoned altogether and replaced as a precursor to building a different kind of economy of people and the planet. We are still a long way from consensus about the right approach. We’re even further away from alternatives being picked up and used in mainstream political and economic discussion.

So how can the debate move forwards?

Looking at the different ways GDP is used can help to distinguish where GDP is particularly useful and where alternatives offer more insight.

GDP is an indicator of the potential tax base and helps identify whether government can afford spending commitments

The question of whether governments can afford their expenditure was at the heart of the earliest efforts to measure economic activity in the UK back in the 1600s. At the root of the government’s blitz of pro-growth messages today is a belief that to be able to spend more we must grow more. Yet this comes at a time when constraints are being imposed on government debt through rising borrowing costs.

The focus of GDP on market activity is helpful for this purpose. After all, it is far easier for government to administer a tax on the sales of goods like clothing than it is on the hypothetical value of housework or volunteering. A narrow, market-focused definition of economic activity such as GDP is likely to remain a particularly important part of our national statistics. Moves to broaden the definition of GDP or use alternative measures are unlikely to be able to meet this need in the same way.

GDP is a measure of social welfare or quality of life

There is good evidence that GDP correlates with a range of measures of social welfare for low-income countries. However, this relationship appears to become significantly weaker as economies become richer. This has prompted calls for alternative approaches for measuring social progress.

One option is to extend GDP by including estimates for the value of activities currently ignored by GDP. This could include imputing the value of household services such as cooking, cleaning and childcare, or the value flowing from access to nature or other resources.

The other option is to measure social welfare directly through, for example, the use of standardised, repeatable surveys of our subjective wellbeing.

The first approach benefits from feeling more familiar and consistent with the measurement of GDP. However, in practice this approach faces a wide range of conceptual and practical difficulties. Any parent will tell you that the answer to whether looking after your children is a childcare “service” or a leisure activity varies dramatically by the minute!

For this reason, the direct approach of measuring wellbeing seems simpler and more democratic, allowing individuals to judge themselves how their life is rather than encouraging statisticians to ‘decide’ what the value of different activities are. The key criticism of this measure is whether it can show enough change over time when viewed at the aggregate level. However, the recent shifts in levels of wellbeing in response to the Covid pandemic highlight that it does move when people experience real, meaningful changes in their lives.

GDP for international comparisons

One of the advantages of GDP is that it enables consistent comparisons between different countries. This can be useful to compare progress over time and empirically test a host of economic theories. It forms the foundation of a wide range of economic research and journalism.

However, despite the UN’s manual on how to calculate GDP now reaching 722 pages there are significant inconsistencies and practical challenges in comparing GDP between different countries.

First, there are a series of adjustments required to make meaningful comparisons.For example, to account for the differences in the proportion of people that own their home (and therefore do not pay rent) or, more controversially, the size of the hidden economy (including prostitution and drug dealing). This can have a significant impact. Italy increased the size of its GDP by more than a fifth in 1987 simply by incorporating a new estimate of its hidden economy.

The next problem relates to how we compare prices in one currency to prices in another. Purchasing Power Parity (PPP) is used to adjust GDP to take account of this.PPPrebalances exchange rates to take account of goods that are rarely traded on international markets and local preferences for food and other household items. Once again, updates to the data and assumptions sitting behind this calculation can make a huge difference to estimated GDP. For example, in 2010, Ghana’s GDP increased by 60%, taking it from a ‘low-income’ country to a ‘middle-income’ country because of a long-overdue update in the data used to assess PPP.

What about other approaches? Are they any better for international comparisons? Adjusted forms of GDP suffer from all the same challenges as GDP for this purpose, potentially further exacerbated by the relatively scarce availability of the data needed to make the adjustments. This means that they are unlikely to help.

Direct measures of wellbeing offer an alternative but also have limitations as the kind of measure we need. The commonly used question of ‘Overall, how satisfied are you with your life nowadays?’ (measured on a scale of 0-10) can be difficult to precisely translate out of English with the same nuance that it might be interpreted in the UK. Can we be sure that the differences in wellbeing measured between one country and another are driven by genuine differences in quality of life rather than driven by linguistic and cultural nuances?

Evidence suggests that a large proportion of the international variation in wellbeing measures can be explained by factors that we would expect to be associated with quality of life, giving us some comfort that many of the differences reflect meaningful quality of life. However, further research could help to refine these comparisons over time, strengthening confidence in measurements

GDP as the basis for productivity measures

Comparisons of productivity – the amount produced per unit of input (often hours worked) – play an important role in policy debates in many countries. Improvements in this metric are seen as essential to long-term prosperity that can support a better quality of life.

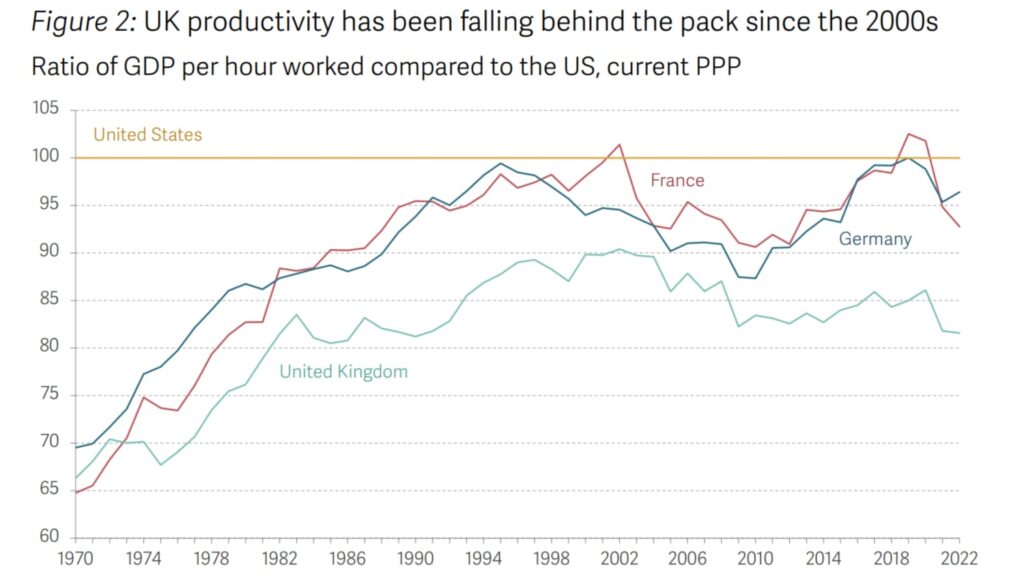

The challenges with measuring productivity are well known and well documented. Many of the GDP measurement issues highlighted above sit at the centre of these difficulties. However, it’s not uncommon to continue to rely on measures of GDP per hour worked. The following chart from the Resolution Foundation’s recent Economy 2030 research programme provides a good example of this. It focuses on how European countries compare to the benchmark of productivity, the USA:

However, if we ultimately care about productivity because it’s an indicator of the potential quality of life, is there a benefit in measuring it directly? If we looked at the same issue from the perspective of wellbeing productivity – how much quality of life is generated for each hour of work – we’d see a different picture.

While this alternative picture still suggests the UK could do better, the USA with its long working hours culture no longer appears to be the global benchmark for performance. This would be a very different way to approach productivity, but there’s no reason it’s any less valid than a traditional approach relying on GDP per hour worked.

Is GDP still fit for purpose?

Overall, we have a mixed picture. Whilst there could be significant value in going beyond GDP for measuring quality of life, there is likely to remain an ongoing role for a relatively narrow measure of GDP to understand the potential tax base of the country. Likewise, for making international comparisons and measuring productivity there are significant challenges with any approach that we currently have available.

This means that “going beyond GDP” is not a single choice or a simple process. There remains a need for something that looks very much like existing measures of GDP, wholesale replacement is unlikely to be realistic or helpful.

Could a dashboard of outcomes be the solution?

If we have a range of needs and a range of potential solutions, does this imply that we need more than one measure to understand “economic progress”? Almost certainly, but how many do we want?

One solution that has been put forward is a dashboard covering a wide range of different measures to give a comprehensive picture of what matters in people’s lives. The ONS UK Measures of National Well-being Dashboard or New Zealand’s Living Standards Framework provide good examples of this.

While this approach is appealing in theory, the practical use of such a complex array of measures for designing policies and communicating priorities is likely to be challenging. On a practical basis, government officials simply do not have time, data or expertise to assess the potential impact of a new policy across so many different dimensions. This means that it will inevitably result in ‘cherry picking’ the most promising indicators for a given policy and ignoring those where there is a stronger trade-off.

A way forward

Limiting the number of progress indicators to a small group of key measures is likely to be a better solution. Following the structure that Amartya Sen and Joseph Stiglitz used in their 2009 review of how we measure economies, a focus around three key areas is more practical:

- GDP-based measures that would serve the need of understanding growth in the market economy (and therefore the potential tax base).

- Quality of life measures such as personal wellbeing.

- Sustainability measures that capture the impact that today’s activity has on future generations and the natural environment.

The communications challenge

There is growing recognition of the limitations of GDP as a progress measure but it’s time for the ‘beyond GDP’ debate to mature. GDP will continue to have an important role in public policy discussions due to its intrinsic link to the potential tax base and servicing of public debt. Ignoring this weakens the case for change. So, instead, this becomes a debate of which other measures can gain a similar level of prominence alongside GDP.

Personal wellbeing measures have an important role for understanding people’s experienced quality of life. But how can wellbeing become established as an alternative way of looking at social progress? There is a big hurdle to overcome to build the understanding of wellbeing amongst political and economic commentators so that it is seen with the same sense of respect as GDP.

This challenge is largely one of communication and PR, not a technical one. How can wellbeing measures, or indicators of sustainability for that matter, be translated into something that has both technical credibility and immediately accessible appeal? If we want to go “beyond GDP” we will need to go beyond the comfort zones of researchers and get creative about how these issues are communicated.

We will continue our work on wellbeing poverty – our attempt to draw attention to the sharp-end of the wellbeing distribution – but we are keen to work alongside other campaigners and researchers in this space to do more.

It will not be an easy process. Competing with a measure that has an 80-year head start will be an ongoing battle. But establishing alternative measures of success in the public debate is a worthwhile struggle, critical to the long-term success of our society.

This article is the first in PBE’s new ‘Economics to improve lives’ series that explores a question at the heart of PBE’s mission: How do we ensure that wellbeing – the quality of life experienced by individuals – is the ultimate goal of government?

We’re bringing together thinkers and commentators from across economics, policy, academia, media and civil society to challenge conventional wisdom and consider how we might build an approach to measuring economic success that puts the lived realities of people at its heart and fits the times we live in.